Rather than a frail pensioner, the People’s Republic of China will be a hard-punching great motherland when celebrating its 70th anniversary on 1 October. Mao Zedong declared the founding of the communist People’s Republic on 1 October 1949, but it is only since 1978 that China has seriously built up economic muscle on its once slight body. That was two years after Mao’s death, when Deng Xiaoping assumed power and introduced economic reforms and the gradual opening up of China to the rest of the world. Since then, more than 800 million Chinese have been lifted out of poverty – a historical achievement. Between 1978 and 2014, China experienced average annual economic growth of close to 10%, and is now the world’s second largest economy after the US. “The Chinese came from a very modest starting point before Deng Xiaoping pressed on the accelerator. In 1978, GDP per capita was considerably lower than the average for the African nations. However, despite its impressive growth rate, China still lies far behind the developed economies, such as the US, Germany and the Nordic countries in terms of GDP per capita,” explains Danske Bank’s investment strategist Lars Skovgaard Andersen.

Why growth has shifted down a gear

China has been the largest single contributor to global growth since the financial crisis, even though the economy has shifted down a gear in recent years. Danske Bank expects growth to come in at 6.2% in 2019. “There are numerous sound reasons for the slowdown. China’s population is ageing and the labour force is shrinking and, furthermore, the Chinese have now harvested the low hanging fruit; the transfer of knowledge from the outside world that can lift production – from here on in, growth will have to be driven to a greater extent by domestic innovation. And finally, growth in China has also been driven by a high level of investment that will be difficult to maintain going forward, as China’s total debt is very much higher now than, for example, 10 years ago,” says Lars Skovgaard Andersen. Nevertheless, growth is still running far above that in the western economies and China’s global significance will only increase in the coming decades, according to our investment strategist. From a wider perspective, the trade war between China and the US is probably just a bump in the road that will generate uncertainty and further squeeze Chinese growth in the short term

An important midget in the equity market

Yet, when it comes to equities, the Chinese equity market is still a midget in a global context. Chinese equities account for just 3.8% of the global equity market (MSCI AC World), whereas the US makes up 56%. However, investors simply cannot afford to ignore China, emphasises Lars Skovgaard Andersen. “All investors should have Chinese equities in their portfolios, so they have direct exposure to this important area of the global economy – otherwise they have a blind spot in their portfolio. We currently recommend a neutral weight in Chinese equities, as the trade war simply means too much uncertainty – and the trade war has hit China harder than the US. That we do not have an underweight is due to Chinese equities being relatively attractively priced in relation to expected corporate earnings, plus they could enjoy a noticeable boost if a trade agreement falls into place earlier than expected,” he says. Despite recent overtures between the US and the Chinese, and a further round of trade talks scheduled for October, Danske Bank’s main scenario is still that we won’t see a trade deal until after the US presidential election in November 2020.

Significant risk premium on Chinese equities

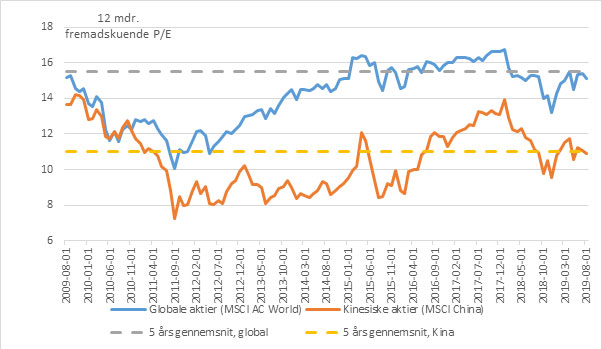

Taking a closer look at the Chinese equity market, the IT and financial sectors currently weigh extremely heavily in the index, led by tech giants such as Tencent, Alibaba and Baidu, along with major banks like China Construction Bank and Bank of China. Another side to the story is that the Chinese equity market also includes many government-owned companies in strategically important areas, such as steel, coal, oil, telecommunications and finance, and they are not necessarily driven only by commercial considerations. They are generally less profitable than private sector companies. Chinese equities have for many years traded with a significant risk premium – ie, at a lower P/E ratio – compared to equities from developed markets like the US, Europe and Japan

More muddied than developed markets

According to Lars Skovgaard Andersen, the risk premium on Chinese equities is due, among other things, to factors such as uncertainty on future growth, less transparency, currency risk and also the ongoing trade war, which regularly generates new political announcements, stories and rumours that affect Chinese equities. On top of this comes the political risk of having a powerful state apparatus with much greater influence on business than we are familiar with here in Europe. “These factors are thus part of the overall package that makes the picture a little more muddied when investing in China. Nevertheless, the risk premium and future prospects are sufficiently attractive, in our opinion, for us to recommend that investors have Chinese equities in their portfolios,” he says.

Did you know that:

- China consumes around half of the world’s cement, iron ore and coal.

- China overtook Europe earlier this decade as the world’s largest beer market.

- Healthcare, technology, education and entertainment are among the fastest growing sectors in China.

- China is very much focused on growth being more driven by domestic consumption and being less dependent on exports.

- China is the world’s sixth largest wine producer – and has ambitions of being the largest

Chinese equities are cheaper

Chinese equities have for many years traded with a risk premium relative to global equities when measured as the 12m forward P/E. Chinese equity valuations are currently on a par with their average of the past five years.

Source: Macrobond.

(12m forward P/E, Global equities, Chinese equities, 5-year average, global, 5-year average, China)

After coming to power in 1978, Deng Xiaoping spurred China from being a government-controlled, planned economy into a mixed economy with a degree of influence from free-market forces. Among other initiatives, collective farming was abolished and farmers got their own piece of land, which led to increased production. The photo shows him hugging former US President Jimmy Carter at a meeting in Beijing in 1987

Danske Bank has prepared this material for information purposes only, and it does not constitute investment advice. Always speak to an advisor if you are considering making an investment based on this material to establish whether a particular investment suits your investment profile, including your risk appetite, investment horizon and ability to absorb a loss.